Physikerinneninterviews - Dr. Ulrike Endesfelder

Interview: Dr. Ulrike Endesfelder

Ulrike is a group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Marburg and member of the German Young Academy. Her group specializes in the in situ observation of molecular processes underlying cellular functions in microorganisms and combines biological research with technological innovation to gain a basic understanding of how complex interdependencies of single molecules enable life.

1. What inspired you to pursue a career in physics?

Influencing (no complete list!) along different stages of my career were:

Superconductivity and my enthusiastic high-school teacher organizing liquid nitrogen for me.

Many stimuli from astronomy, e.g. “measuring the universe”, a summer course for high school students, gravitational lensing observations and new data on the cosmic microwave background coming up during my under-graduate studies, a student internship at the MPI for radio astronomy exploring star forming regions and many more.

Ferrofluids and their unexplored behavior under low gravity. This resulted, also thanks to many people helping and supporting us, a team of students, in a 120 kg heavy experimental setup around some milliliters of ferrofluid for a zero-g parabolic flight campaign!

And of course biophysics - especially my first time seeing single molecules at work, namely ATP synthase rotation and myosin walks and shortly after the development of dSTORM, a single-molecule super-resolution microscopy technique.

2. Who are your role models?

No single person really – rather a cumulative sum of different influences (see No. 1)! As a student I was interested and focused on science. Thus:

Students and PhDs: go for scientific research – explore and enjoy, challenge your teachers, be unconventional!

To all Post Docs and starting group leaders: This is a very short but highly defining time for your career! I strongly encourage you to talk and reflect a lot with others – find peers, mentors, advisors, and interested friends: if there is a new situation – reflect, decide and take action! And talk to more than just one person, for all the different situations and occurrences just pick the best fitting conversation partner(s). But only people of trust ensuring confidential settings!

To all scientists: challenge your awareness, (self-) reflect regularly and critically! Get involved in science policy which sets the frame for our daily professional lives and don’t leave the important policy topics shaping our academic world to just a handful of people.

3. How did you get to where you are in your career path?

No spectacular but steady career steps: I studied in Bonn and Stony Brook, finishing off with an external diploma thesis at the Caesar research center in Bonn, and then I went to Tokyo for a short research stay, followed by PhD and Post Doc times in Bielefeld, Würzburg and Frankfurt. For three and a half years I have been now a project group leader at the MPI here in Marburg. If you are interested in particular or more details, just contact me!

There is maybe only one in general interesting note about my individual path which younger academics are maybe not aware of but which has not insignificant impact: I was not abroad for a longer time period after my PhD - but: (1) Many current grant schemes for starting PIs as well as some members of evaluation committees (even though this is always individually different and scientific culture is ever changing!) have criteria that demand for a longer time (normally at least one year) abroad *after* your PhD – this has cost me several opportunities. (2) Your academic time on temporary contracts in Germany is currently limited to 12 years by the “Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetz”. But in practice there is - in most cases - no permanent position available at your institute which would back you up. In real life this just means that your academic time is ticking and constantly counted up as long as you are in Germany (and on a temporary position, thus in practice every position before being appointed to a professorship). Not “extending” my time by going abroad left me with in total significantly less time to qualify for a professorship compared to a substantial number of peers. This 12 years’ time is short to qualify and the number of available professorships is low (current numbers are e.g. about 1 out of 7 junior faculty members get a professorship (numbers can be found e.g. in BuWin 2013, p. 132-133, 136, 157, 166, 172, 182; discussion of these numbers in Menke, Schularick, Baumbach, Wolf et al, 2013, ISBN 978-3-00-044145-5, p. 6)), the average age of first professorial appointment is 41.4 years (BuWin 2013, p.177-178)! Also processes are often slow: even if you yourself are confident that you can be fast, the surrounding may be limiting, e.g. time for publication or grant reviews or fixed yearly or even biannual deadlines can and will not be sped up for you. That being said: I was aware of both when I made my Post Doc decisions and luckily I am still convinced that these decisions I made back then were best for my individual career.

Maybe more general: It’s important to say that I got to where I am in my career by a 50/50 between internal and external influence:

From my side: by my motivation(s), 50/50 of naiveté and rational reflection and in the end stubbornness and resilience - and concerning high impact decisions: my strong trust into my intuition. More details? I happily share them in personal contacts!

From the others’ side: by fascinations and interests of inspiring companions! I luckily almost always in my life could rely on an extraordinary crowd as peer group – my fellows during my studies, my PhD and Post Doc colleges, networks, e.g. the CdE and the young academy or also strong mentors and institutional influence, e.g. my PhD advisor or currently the community here in Marburg. And last but by far not least: the people of my private life who stably survive and comfort me in all my stressy moments – a powerful reinforcing element.

4. What is the coolest project you have worked on and why?

That’s simple, the two endeavors I am most grateful for and with the steepest and most-all-encompassing learning curves:

For one, as it was the by far most influencing project when I was a student: the already mentioned zero-g parabolic flight campaign project which we realized under an extreme short amount of time from scratch, managed all checklists and safety measures … and actually boarded and flew (Figure 2).

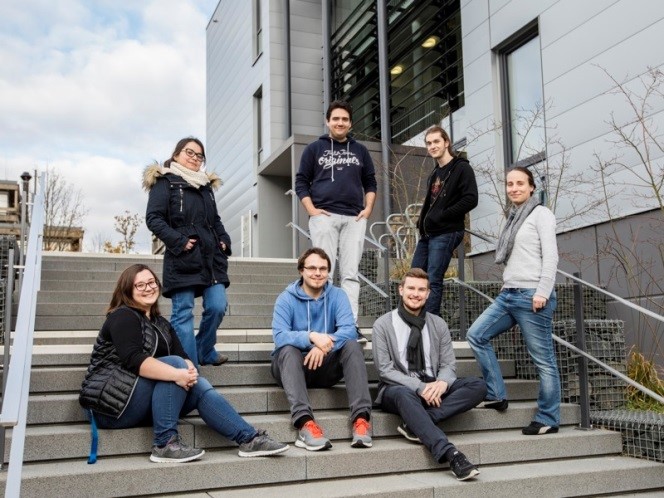

And second: the endeavor to set up a research group! Every day new setbacks and successes – mostly small but all impacting, diverse and often unexpected, internal and external, positive and negative, that often enough cannot be controlled or avoided – but in total so much rewarding to see the group and individual students advancing into such a well-tuned scientific team (Figure 3).

5. What’s a time you felt immense pride in yourself / your work?

My emotional pay back is seeing the highly engaged and proud, big smile and at the same time relief of my people when their experiments work out or results get published.

6. What is a “day in the life” of Ulrike like?

That’s one of the things I adore about my job and is actually one of its inherent characteristics: None is alike!

To give an impression, here a link to a recent twitter post I had in my twitter stream which nicely illustrates the statistics.

7. What are you seeking to accomplish in your career?

Science: maybe, a truly extraordinary discovery lies hidden for us in the future or maybe just a lot of small steps steadily but slowly advancing our knowledge – I guess I always will be driven by my curiosity on how the complex interdependencies of single molecules enable life! And I have plenty of worth-it-to-try-ideas in my head!

Mentoring and leading: I will to do my very best to always inspire and lead a small bunch of happy, young scientists (I am for a lot of reasons no fan of too big research groups)!

8. What do you like to do when you’re not doing research?

Oh, a great deal of different things but I can’t report a magic secret ingredient for perfect happiness – I am trying to balance a bunch essentials and excitements that complement my work life. Every time I change the city there are new stimuli and cool to-dos around while old ones are left behind. E.g. in Würzburg I got expertise in white wine, from Frankfurt my love for art museums, and after a year of living in the rather hilly area of Marburg, I bought an e-bike with which I easily explore the surroundings. Also, I now conveniently arrive at work after only 15 minutes biking uphill along a forest trail every day.

9. What advice do you have for other women interested in physics?

Go for it! (and see answers no. 2 and 3 – in case of any doubt: reassure yourself and overcome obstacles by regular exchange with others!)

10. What should be done to increase the number of women in physics?

Strongly depends on which stage of career. One of the top to-do-points on my bucket list after ensuring a stable and no longer only temporary place for my group is actually to convert my experiences into explicit proposals for improvements (I believe that written-up summaries are actually not the most impacting way and I am collecting ideas, so please feel very welcome to contact me!). I think it’s important to help future early career scientists to more quickly and easily understand the conventions and habits of scientific business. I do my best to actively remember my experiences - before I get too accustomed and forget how bizarre they actually often are and how often I was doing the right thing by sheer luck without knowing in advance.

Maybe one general thing – again (see answer no. 2) increasing awareness! Everybody (scientists, students, stakeholders, communicators etc.) should avoid interacting with females under gender preconceptions and stereotypes and should be (self-) aware of those! In my opinion one of the largest unconscious bias barriers to pass lies within our societal stereotype of a high-profiler leading person (-> test yourself: what kind of person comes into your head when you imagine e.g. a “strong leader”?). Being labeled by different stereotypic societal descriptors and thus being perceived and addressed differently than men influences and thus holds many women back every single day of their life (from childhood on!) and thus ultimately in their career, e.g. in being regarded competent (as well when judging themselves), in evaluating their work during publication processes and subsequent apparent impact of their research, in getting positions, in being heard in meetings and committees, in being honored by invites to conferences, in successful grant writing, in media coverage and many more. These effects in everyday life, which usually are almost insignificant by themselves, nevertheless have a strong cumulative impact. There is reason why academia loses most females during PostDoc/early group leader/assistant professor phase. For example, there is a high rate of “she is too young”, “not ready yet” (e.g. for an independent position etc.) while “her” cv actually equals male counterparts – until “she” is actually running out of time and money (e.g. early career grant schemes and positions are usually only 2-7 years after PhD) or leaves academia due to too high frustration… And very importantly: our bias is not limited to women only - awareness is needed for increasing diversity in general!

Foto-Rechte: (1) Ulrike Endesfelder, (2) Ulrike Endesfelder, (3) MPI Marburg

The interview has been carried out by Dr. Ulrike Boehm, member of the AKC. If you have any questions, feel free to contact her .