Physikerinneninterviews - Dr. Cornelia Hofmann

Interview: Dr. Cornelia Hofmann

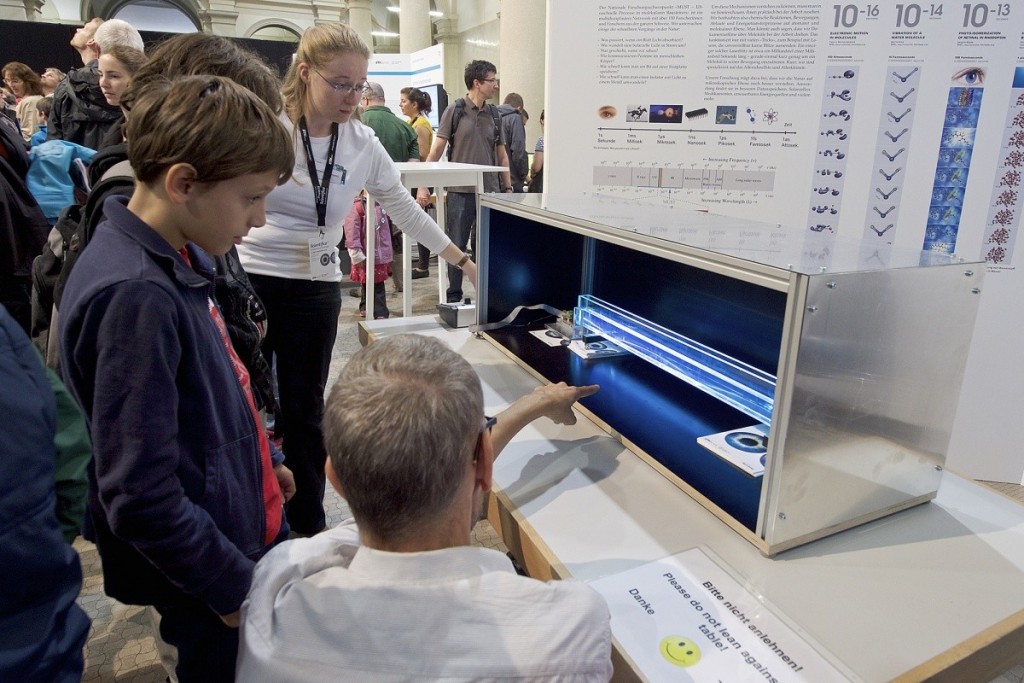

Cornelia is a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems in Dresden. She studies the interaction of strong ultrafast laser pulses with atoms, which allows them to investigate electron wave packet dynamics both during the strong-field ionization process and during the subsequent propagation of the photoelectron. Ionized photoelectrons can take part in many different phenomena, such as creating highly excited Rydberg states, or contributing to High Harmonic Generation. This fundamental research helps understanding ultrafast charge transport in a variety of process, for example during chemical reactions or in photovoltaic cells.

1. What inspired you to pursue a career in physics?

I always had very broad interests during my school time, and with my hobby choices. I enjoyed learning and discovering new things, virtually irrespective of the topic area. Questions like “How does this work”, “how is that built”, “what’s the function of ...” were constantly on my mind. Over time I noticed that structured approaches such as Grammar studies in languages, or systematic exploration of a question in natural sciences were the best outlet for my curiosity. Finally, a career consultant specialized on higher education paths managed to distill all of this into the simple conclusion: I should study physics.

The higher I progressed in my study program, the more I enjoyed the subjects, classes and research experiences, so that continuing for a PhD degree was the logical next step. Since then, I have continued with the promise to myself that I would pursue this career for as long as I found fascinating research topics and positions.

2. Who are your role models?

I do not think I have a clear role model when it comes to researchers. But the more I learn on the topic, the more grateful I am to my parents and grandparents. They always made sure that I and my brothers had all opportunities, and we all learned the same skills from them, be that building an electric circuit, knitting and sewing, or playing an instrument.

3. How did you get to where you are in your career path?

For my school years 9-12 at a state school for higher education, I had chosen Latin as my specialised subject. So when I first started my Physics Bachelor program at ETH Zürich, I was nervous about how much of a disadvantage I would have, being a “language major” previously. But I lost that fear pretty quickly, when I noticed that the progress in the first year (predominantly maths subjects for a solid background of tools later on) was so fast that “physics/maths majors” had lost their advantage within a couple of weeks.

During the Bachelor and Master programs, I noticed that my colleagues would know my name much more often than I knew theirs, most of the time I could barely figure out which class we were sitting in together. But that was the only real consequence of the strong gender imbalance in our program.

After attending “Laser-Atom-Interactions”, a tiny and highly specialised class during my Master degree (which I had chosen purely based on the synopsis), I was offered a Master thesis project, and finally even a doctoral position. So I have to thank Dr. Alexandra Landsman, then a senior researcher in the group of Prof. Ursula Keller, ETHZ, for getting me started in the field of attosecond science.

Through her move to the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (mpipks) Dresden, I also got the opportunity to visit mpipks on a mobility grant. This visit, in turn, paved the way for my current postdoc position at mpipks.

Following my passion for teaching (and tutoring on the side), I also decided to study for a teaching diploma for physics in secondary education levels. In parallel to my Masters and doctoral education, this gave me another viewpoint on physics in general, as well as training my skills in communicating also my own research results.

The higher I got on the academic ladder, the more I noticed gender-related issues. Thankfully, my PhD group was embedded in a research network that pursued a proactive approach to supporting women in the field. So I had the opportunity to participate in special training and workshops, and educate myself. The simple existence of these offers also sparked many discussions in the entire group. And being aware of these issues is, of course, a prerequisite for any progress to be made.

4. What is the coolest project you have worked on and why?

I cannot choose a favorite project. Each project has some aspects that I really enjoyed/loved/found cool about it. Starting from working on Uranium isotope mass spectroscopy for water probes from the Atlantic, via following photoelectrons on their journey to ending up in a highly excited bound state, to working on the temporal resolution of processes on the fastest timescales currently possible in the world.

5. What’s a time you felt immense pride in yourself / your work?

Holding a stack of my nicely printed thesis books is definitely a great feeling of accomplishment. But on a smaller scale, time and time again there are small Eureka moments, when a quick calculation on a scrap paper returns the desired result, when a code runs for the first time without an error, when a colleague at a conference comes to me to ask for my insight, ...

6. What is a “day in the life” of Cornelia like?

As a theoretical physicist, the majority of my days I spend sitting at my desk. I typically start by sorting out emails that have come in since I last checked. Then it’s a combination of writing (and a lot of adapting) code, analysing data, implementing different theories to compare, writing up summaries, reading papers related to my research, meeting with my coworkers for updates on our projects, and helping PhD students along in their projects. Scattered in between there are group meetings and seminars to attend, and talks or posters to prepare for upcoming conferences.

7. What are you seeking to accomplish in your career?

Research-wise, I want to contribute to the understanding of the interaction between light and matter at the most basic level. While I keep following this goal, my academic career must naturally progress as well. How far that will reach remains to be seen.

8. What do you like to do when you’re not doing research?

A big hobby of mine, and my method to keep my head from spinning out of control under pressure, is music, in various forms. Playing instruments, singing, or listening to music can reboot my energy, and boost my mood.

Besides that: reading novels, learning new languages, sailing when I find the time, occasional cycling or hiking tours, and some snow sports in the winter, are ways to occupy my mind with something other than physics.

9. What advice do you have for other women interested in physics?

Go for it! Find topics that you enjoy working on. Any topic that fascinates you, can keep you hooked on a problem so much that you forget time passing, that will keep you motivated and drive you to keep going. Connect with supportive peers. Keep your eyes open for targeted supportive measures and make use of them (their purpose is to try and even out a slanted playing field, after all). And in case something does not feel right, then find a person you can trust to talk through it. Also, check your own unconscious bias, and make an effort to fight it.

10. What should be done to increase the number of women in physics?

Phew, there are so many different knobs to turn here. Two examples that are important to me, personally:

On the level of school education: Teachers must constantly be aware of gender stereotypes, and actively check themselves, their interactions, their teaching methods, and content presentation. On the level of academic institutions: Equal treatment policies collecting dust on paper are not enough. Their implementation must be noticeable in the daily life at an institute.

Preferably, that would include gender training (what is the status quo of the gender imbalance, what is unconscious bias and how can it be fought, ...) on a regular basis for all members of the institute.

Foto-Rechte: (1) Cornelia Hofmann, (2) D-PHYS/ ETH Zürich Heidi Hostettler, (3) Cornelia Hofmann

The interview has been carried out by Dr. Ulrike Boehm, member of the AKC. If you have any questions, feel free to contact her .